Key Findings

The global online gambling market is growing faster than regulatory and health responses. This has prompted stakeholders, including giants with significant market power such as MGM Resorts International, to increase their advertising expenditure, from $235 million in 2022 to $299 million in 2023, a 53% increase [1]. This growth comes with the worldwide market value expected to hit nearly $120 billion by 2026 [1].

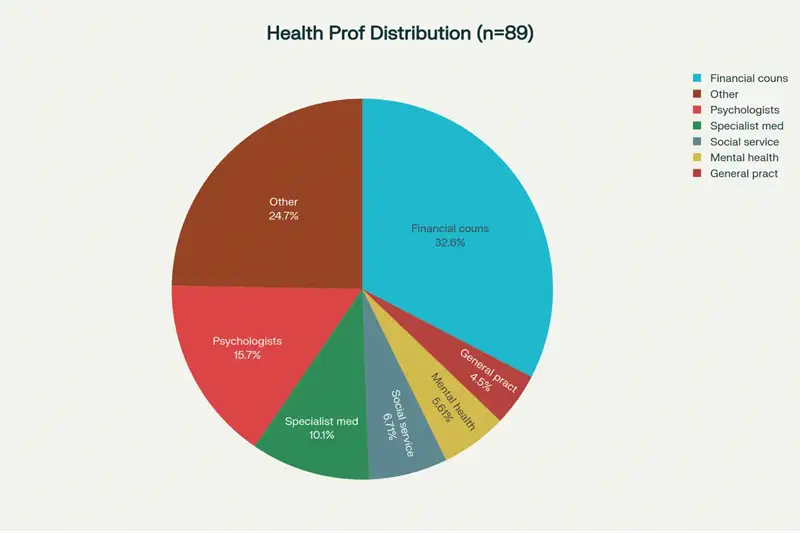

But this boom is mirrored by a worrying healthcare challenge. A small (n = 89) recent sample of health and community-based healthcare providers found that 25.8% had never received targeted training in identifying gambling-related issues, although 85% discussed gambling problems with clients [2]. The greatest proportion of the sample who engaged with gambling issues were financial counsellors (32.6%), suggesting that most individuals were intervening only after financial problems.

The absent explanatory link is supplied by cognitive psychology. From the (in)famous example in Monte Carlo, where players lost millions by assuming that if there were 26 consecutive black the red is more “due”, and since other biases such as hot-hand belief, gambler’s fallacy, and clustering illusion are well documented in literature [3][4], the gambling industry has used and abused these phenomena [5]. Due to these cognitive biases and the immersive nature of VR/AR technologies and mobile platforms, users are vulnerable to impulsive and error-based processing.

Our analysis integrates three domains:

The core of the argument becomes obvious: the growth of online gambling is not coincidental but structurally reliant on gaming cognitive biases, whilst the healthcare mitigation measures lag behind. Unless immediate action is taken, especially in the training of healthcare providers, policy regulation, and technological surveillance, the gap between market sophistication and mitigation will continue to grow, with devastating social and economic consequences.

This report leverages integrated conceptual data extracted from Mordor Intelligence (2025) [1], Heath & Santos (2025) [2], and Gupta (2025) [3], as well as common baseline behavioral research [4–9], in order to scrutinize the systemic dynamics at work.

The global online gaming market growth continues to proliferate, fueled by technology and advancements in regulations, with fierce competition amongst the major players. The market is projected to be worth $260 billion USD in 2025, with a CAGR of 10% between 2021 and 2025 [1].

Market Segments:

Geographic Distribution:

Mobile gambling already represents over 60% of all online gambling, and this percentage should continue to grow with the increasing prevalence of consumer-oriented design via mobile-first strategies [1]. In the case of hardcore or “professional” gamblers who are doing high-level betting analysis, desktop platforms are needed.

Market concentration is still high since it’s dominated by 888 Holdings, Betsson AB, Kindred Group, Bet365, and MGM Resorts International [1]. Competitive advantage exists with tech innovation, ease of use of the platform, and integration into the marketing strategy.

Market Growth and Advertising Investment (MGM Resorts 2019–2023)

| Year | MGM Ad Spend (USD Millions) | YoY Growth (%) | Market Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 195 | – | Pre-pandemic baseline |

| 2020 | 88 | –54.9% | COVID-19 impact |

| 2021 | 121 | 37.5% | Recovery phase |

| 2022 | 235 | 94.2% | Acceleration begins |

| 2023 | 299 | 27.2% | Peak investment |

Source: Company financial disclosures; compiled in Mordor Intelligence (2025)

Since the coronavirus pandemic, the gambling industry’s recovery plan has heavily relied on one strategy more than any other: advertising. Instead of concentrating on operational safeguards or consumer protections, big operators lavished funds on high-profile marketing campaigns to increase the sector’s profile and make gambling an acceptable part of daily life.

One of the most clear-cut examples is from India, where Fairplay’s “Khel Ja” campaign used celebrity endorsements to try to depict gambling as a routine, aspirational leisure activity. By connecting betting to pop culture and star power, such ads blurred the distinction between entertainment and risk, and nudged public perception of gambling. There are equivalent strategies across the globe, with marketing campaigns developed to integrate gambling into familiar social narratives.

The financial investment into these campaigns is intense. MGM Resorts International data depicts an outright lift-off of advertising expenditures that starts while consumers are still emerging from pandemic lockdown. This wasn’t just an effort to recover. It was an attempt to prime new demand by bombarding consumer environments with messages about gambling. This way, advertising became the industry’s recovery engine.

Technology has magnified this effect. And with new VR/AR categories allowing gambling firms to completely replicate casino arrangements in the digital realm, advertisements can be an experiential rather than a passive sales pitch. These are not simply promotional tools; however, they are integrated into the fabric of gambling environments, such that the marketing message becomes inherently linked to the act of play.

Meanwhile, the transition led to mobile-first engagement that has created new opportunities. Sportsbook operators now use custom push notifications, in-app offers, and AI-driven suggestions, so that players can bet multiple times. Studies indicate that such strategies stoke engagement and spending in meaningful ways, further underlining just how inextricable advertising has become from platform design.

Collectively, these trends indicate that the rebound of the gambling sector from COVID-19 has been less about operational hardiness and more about the rapid intensification of the marketing onslaught. Celebrity endorsement, technological immersion, and mobile optimization have meant that advertising is no longer just about visibility. It is now the primary means through which gambling is not only normalized, but maintained and expanded.

Interpretatively, this indicates an industry whose growth model is structurally situated outside of economic fundamentals, and instead depends on psychic-captures. After a slight dip during the pandemic year of 2020, MGM ramped up its marketing spend dramatically through 2023. The development demonstrates how the focus for post-COVID recovery strategy in the gambling industry has shifted from operational adaptations to advertising muscle.

Knowing who is at the front line for identifying and treating gambling-related harm is an important part of designing effective interventions. The analysis included 89 respondents from health care, mental health, and social service environments, showing a varied mix but a limited presence of competency.

Financial counsellors made up the largest group (32.6%), reflecting the financial ruin often associated with gambling. Their prominence shows that harms are more likely to be discovered through debt and economic instability rather than medical or psychological channels. The reliance on financial experts as gatekeepers highlights the need to incorporate the clinical view in early screening.

Psychologists (15.7%) offered an important perspective on cognitive and behavioral elements. Specialized health care providers (10.1%) were similarly significant, with gambling-related problems often emerging when treating secondary health problems such as stress-related illness, cardiovascular strain, or substance use disorders.

Social service workers (6.7%) and mental health counsellors (5.6%) contributed smaller but valuable shares. They are well placed to recognize harms like family disintegration, homelessness, and psychological pain.

General practitioners (4.5%) were underrepresented, suggesting that gambling-related harms are under-detected in routine practice, though early identification could prevent escalation.

The minority in the ‘Other’ category (24.7%) indicates the multi-sectoral context of gambling harm interventions from community to specialist addiction services. While this diversity is encouraging, it also highlights a lack of consistent responsibility for screening and referral.

In terms of screening behavior, the data shows an anomaly: those most exposed to gambling-related harm (e.g., GPs, mental health workers) were the smallest fractions of the professional cohort, while financial counsellors—though less trained in health aspects—were the largest.

The results indicate a lost opportunity for systematic screening capacity. Without better integration of gambling harm assessment into primary and mental healthcare, affected persons may be identified too late—once financial ruin or severe psychological distress sets in. Screening protocols should be established across frontline services, especially for general practitioners and mental health practitioners. The evidence suggests that gambling harm is most likely encountered by money advisers because money-related harms become evident earlier than health-related harms. This represents a model of damage response rather than prevention.

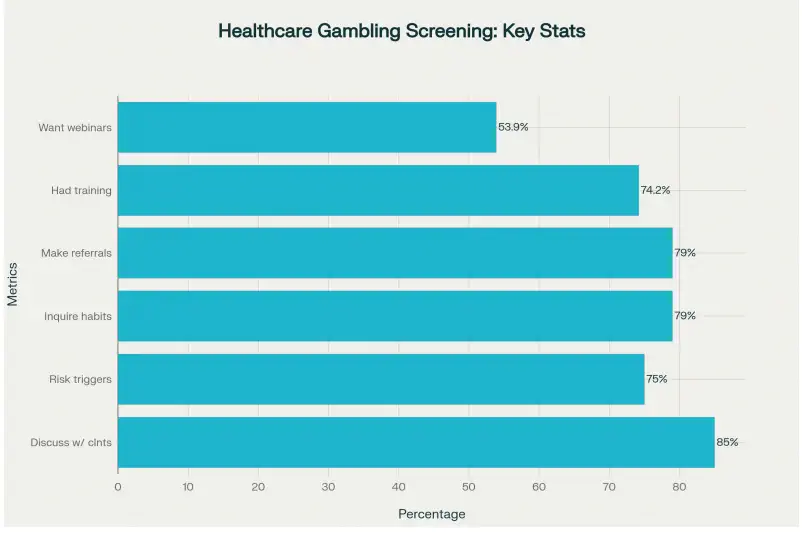

Screening statistics show that most professionals engage clients in gambling, but usually in a reactive way. 85% said they speak to clients about gambling. 75% are triggered by specific risk factors such as financial strain, relationship discord, or substance misuse rather than through routine screening. 79% reported directly asking clients about gambling activity, and the same percentage reported making referrals, demonstrating the availability of a referral network.

Nevertheless, referral effectiveness depends on regional resources and specialist service availability. 74.2% had received prior gambling harm training, indicating that formal education builds confidence in screening. 53.9% preferred online webinars for future training, showing demand for flexible, digital development. Combined, the data show an industry that is active but lopsided. Most are comfortable inquiring about gambling, but reliance on risk signals and fragmented referral systems highlights the need for formal protocols. Expanding access to scalable online training could help embed gambling screening as standard practice rather than a crisis response.

Healthcare responses remain disjointed, with training deficiencies reducing intervention capabilities. The findings can be interpreted through the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), which reflects that attitudes, social norms, and perceived control shape behavior. In this study, perceived behavioral control was the strongest predictor of screening. The more comfortable practitioners felt asking about gambling and handling responses, the more likely they were to screen regularly. This highlights the need for both skill and confidence building.

Peer and organizational support also mattered, aligning with TPB’s social norms. Practitioners who felt supported by colleagues or culture were more likely to engage in screening. By contrast, client expectations were not a significant predictor; even when clients were open to discussing gambling, professionals did not necessarily act. Knowledge levels also showed no correlation with screening frequency, reinforcing that information alone is insufficient without confidence and organizational backing.

Uncertainty around effective implementation was a common impediment. Some respondents reported being unaware of validated screening tools [2]. Unlike alcohol or drug misuse, gambling-specific instruments are less well known, leaving practitioners unsure of best practices. Even when tools exist, a lack of training in sensitive questioning makes providers hesitant, fearing damage to therapeutic rapport or inhibiting disclosure. Concerns were also raised about monitoring digital gambling, including mobile apps, esports betting, and cryptocurrency [2]. The result is inconsistent practice: some rely on intuition, some ask casually, and many wait until harm is visible.

Reducing uncertainty requires not only making tools available but ensuring professionals know how to use them confidently [2]. Even after harms are identified, referral pathways remain unclear. Many professionals knew only a few local services. This limited knowledge, combined with concerns about quality, waiting lists, fees, and geographic barriers, often led to hesitancy [2].

Privacy and confidentiality were also sticking points, as clients may resist disclosure. Cultural appropriateness was another barrier, with existing services not adequately meeting the needs of diverse populations [2]. This mismatch discouraged referrals and reduced client participation. For the continuum of care to improve, clearer referral systems and culturally appropriate materials must be available [2].

Beyond tools and referrals, professionals faced motivational and systemic barriers. With short consultations, they often prioritized other risks such as alcohol misuse, smoking, or depression [2]. Gambling seemed secondary, as its harms are less immediately obvious. Organizational constraints added to this, with little institutional reinforcement, since gambling is not part of many intake assessments or performance measures [2]. Fee-for-service models further reduced time for in-depth discussions [2].

Societal normalization also played a role. Widespread promotion through commercials, sponsorships, and digital games reduced the sense of urgency among both clients and practitioners [5]. This normalization made proactive screening appear less pressing.

These systemic disincentives have pushed gambling screening to the periphery of healthcare. Without stronger resources, institutional backing, and policy support, even trained professionals struggle to prioritize it. The obstacle lies less in knowledge and more in the broader healthcare context [2][5].

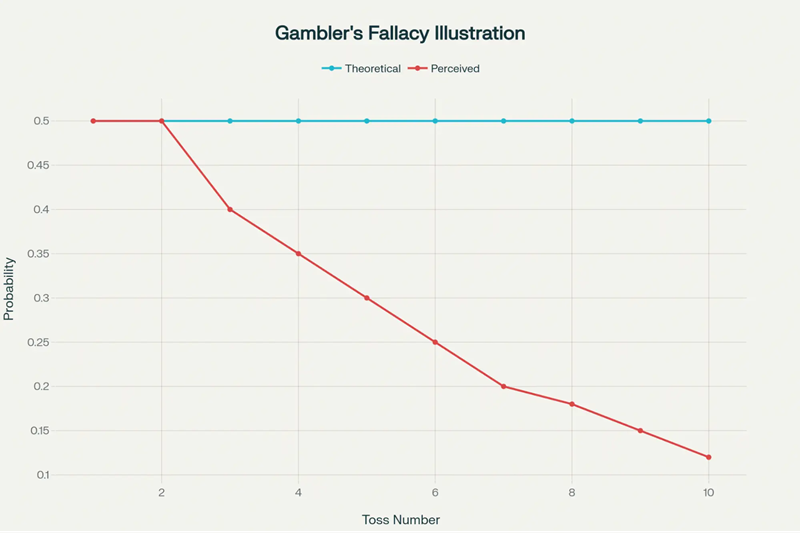

The gambler’s fallacy is the belief in the mistaken notion that random events are self-correcting; that a pattern of events can change to a different pattern in order to balance out [6]. This misbelief is based on the misunderstanding that randomness also involves balancing and justice correcting itself over time. The most common example is the fair coin toss: if a coin toss results in heads five times in a row, most people believe that tails is now more likely. Mathematically, of course, the probability of heads or tails on any given flip is still exactly 0.5, no matter the previous result [7].

One of the most widely known displays of the gambler’s fallacy happened in Monte Carlo in 1913. The ball comes up black 26 times in a row during a game of roulette [8]. Convinced red was due after so many blacks, players wagered heavily on red, losing “$10,000,000, or thereabouts,” in the process. As remarkable as the streak may have seemed, probability theory tells us that such streaks, while unlikely, are perfectly possible in large collections of random events. The illusion is due to human intuition being unable to understand how big streaks are compatible with the laws of chance.

These sequences can be described mathematically using the binomial distribution. So, for instance, if you flip a fair coin 1,000 times, the distribution tells you not only how common heads and tails should be overall, but also the expected length of the streaks [7]. Long runs (eg, six, seven, or more of the same result in a row) are statistically unavoidable in a big trial. But people too frequently look at such streaks as “unlikely” and read them as a sign that the result must turn around. It’s this gulf between expectation and intuition that gives rise to the gambler’s fallacy.

This paraphrased example can easily be visualized through a dual-line graph representing the two models of probabilistic thinking. The theoretical line always lies fixed at 0.5 per coin toss, yet the perceived percentage changes as the length of the streaks crowd out the theory. For example, many gamblers incorrectly give tails a probability of 0.7 or more after five consecutive heads. The discrepancy between the flat, non-changing mathematical probability and the increasing subjective (perceived) probability of winning clearly illustrates the basic error of the gambler’s fallacy.

Above all, the gambler’s fallacy embodies the conflict between statistical thinking and what goes on in our minds. But in maths, independence reigns, while we mortals are very easily seduced by patterns, equilibrium, or a skew to invert, in the random. And this disparity has certain practical consequences, such as in gambling situations, where the notion of self-correcting chance causes people to make ever riskier wagers.

That dissonance — between likelihood and belief — is not accidental. It is carefully engineered in gambling environments, from roulette wheels to slot machines, where visual and audible stimuli enhance the illusion of “due” outcomes.

The gambler’s fallacy is more than a cognitive curiosity; it has been documented and exploited for centuries. A well-documented example of the former is the occurrence of 26 consecutive blacks on a roulette wheel in Monte Carlo in 1913 [8]. As the losing streak on red continued, the players became convinced that red was “due” and kept increasing their bets due to a misunderstanding of the gambler’s fallacy in reverse, which led to the heavy financial losses. This act lives on as one of the most famous examples of how intuitive failings in assessing randomness can have disastrous real-world consequences.

The bedrock of the theory—pioneered by 17th-century mathematicians Blaise Pascal and Pierre de Fermat—was to address fairness in games of chance [9]. They focused on independence and expected values—they were directly rebuking the sort of reasoning that’s at the heart of the gambler’s fallacy. And yet, after millennia of more or less sensible mathematical revelation, gamblers have insisted on believing that they know something about the future that will solidify the present.

Modern casinos are keenly aware of this psychological quirk. Roulette tables, slot machines, and even lottery layouts all take advantage of streaks and near-misses to foster the illusion that outcomes are self-correcting. This exploitation has now gone digital. Online technologies use algorithmic randomness and persuasive interface design to enhance recognized patterns and reify the sense of control and inevitability [10]. So as much as the misattribution of chance in the original forms of gambling, it lives on — reinvented and amplified by technology.

Although the gambler’s fallacy is a well-known artifact of casino play and coin flips, similar cognitive biases manifest in countless other areas of human decision-making. These delusions are symptomatic of the same deeper bad habit: the misinterpretation of random events as predictable ones, with an order or symmetry or defense mechanism that doesn’t actually exist.

The consequences go beyond lost bets, however, into sports, finance, medicine, law, and weather prediction. In sports, the “hot-hand fallacy” is the idea that coaches and fans think a player who has been hitting well recently is more likely to hit well in the future as well. Gilovich, Vallone, and Tversky (1985) demonstrated that such streaks are primarily statistical illusions, but they still affect substitution patterns and playing strategy [11].

In financial markets, the gambler’s fallacy prods investors into anticipating reversals following streaks. Barberis and Thaler (2003) presented that market participants tend to overreact toward recent runs and buy after price drops or sell after price increases, which leads to price volatility [12].

Medical decision-making is equally vulnerable. That kind of thing can feed into the clustering illusion, cause doctors to see random clusters of symptoms or of test results as patterns, proof of something that will justify overdiagnosis. This bias can result in overtreatment and heighten patient anxiety [13].

The law also mirrors cognitive distortions. The fallacy of regression biases judges and juries toward attributing changes in behavior or rates of crime to treatments, causing decisions about sentencing to be wildly inconsistent [14]. Even in daily life, the weather is perceived through a lens of bias. Studies of meteorology have found that people commonly detect such illusory patterns—the mistaken belief, for example, that it is “due” to rain after a sequence of dry days—despite the fact that each day’s weather is relatively independent [15].

These instances demonstrate how one kind of cognitive bias applies widely, bending thinking and leading to substantial real-world consequences.

Applications of Fallacy Bias Across Domains

| Domain | Bias Type | Real-World Impact | Research Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sports | Hot-hand fallacy | Substitution & strategy errors | Gilovich et al., 1985 [11] |

| Finance | Gambler’s fallacy | Post-streak buying/selling | Barberis & Thaler, 2003 [12] |

| Medical | Clustering illusion | Overdiagnosis & overtreatment | Clinical studies [13] |

| Legal | Regression fallacy | Sentencing inconsistencies | Legal psychology research [14] |

| Weather | Pattern seeking | False recognition of cycles | Meteorological studies [15] |

The gambling industry is growing rapidly through technological advances and the exploitation of cognitive weaknesses. With immersion and accessibility increasing, players are more susceptible to psychological triggers that influence their actions. The convergence of invention and bias manipulation underscores a widening gap between industry complexity and consumer defense.

This trend is evident in virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) technologies. VR recreates the sensory experience of a bricks-and-mortar casino, making players emotionally invested and prone to biases like gambler’s fallacy and the illusion of control. Arbitrary events feel “real,” and players buy into patterns or streaks that do not exist. While the technology blurs the line between virtual and physical, it also amplifies irrational betting behavior.

The move to mobile format spread bias-based betting more rapidly. With smartphones, wagers can be made anywhere, anytime, with little time for reflection or self-control. This instant availability drives impulse betting and errors such as chasing losses. Celebrity endorsements further strengthen these effects. By associating gambling brands with popular, respected personalities, companies exploit authority bias—the tendency to follow those seen as credible or successful. For younger generations, endorsements by celebrities make gambling appear legitimate and aspirational while obscuring potential risks.

At the heart of these strategies is a lack of strong consumer protections. Operators use behavioral analytics, persuasive design, and psychological tactics to drive engagement, while regulators struggle to keep up. They profit from engineering environments that amplify biases, and consumers lack defenses to counterbalance those forces. The growth of the gambling industry cannot be separated from its success in exploiting cognitive vulnerabilities.

One of the more worrying consequences of gambling’s spread is that healthcare screening procedures lag behind industrial growth. Despite heavy investment in marketing and technology, there is no equivalent commitment to training health professionals to support people experiencing gambling-related harm. This imbalance creates a vacuum: the industry incentivizes engagement, while health services remain underprepared in prevention.

The timing of the intervention is a key weakness. Financial and mental health counselors rarely see gambling problems until they are severe. By the time people seek help, many have accumulated debts, damaged relationships, and emotional issues. This reactive approach leaves destruction to be treated instead of avoided.

Patterns of professional specialization also reflect structural challenges. Psychologists, GPs, financial counsellors, and problem gambling workers often deal with harm at different stages. Without organized training or standard screening guidelines, they miss chances for early detection, and harmful behaviors continue unchecked.

Normalization feedback makes this worse. As gambling becomes integrated into daily life through mobile play, sports sponsorships, and digital advertising, it loses its stigma. Behaviors once seen as risky are redefined as ordinary leisure. This normalization blurs the line between casual play and harmful patterns, making effective early screening less likely.

Taken together, these dynamics reveal a systemic weakness: the gambling industry expands aggressively while healthcare systems remain underprepared. Until investment in training, early detection, and coordinated intervention catches up with the sophistication of gambling promotion, the gap between industry growth and consumer protection will continue to widen.

An effective healthcare response to gambling harm cannot rely on piecemeal interventions; it needs an overhaul of how health professionals are taught, how at-risk people are identified, and how those already harmed are assisted to access care. Three priorities are pressing: workforce training, coordinated screening, and strong referral pathways.

All professional training must shift from teaching about gambling harm to practice-centered doing. Many health professionals are aware of gambling harm but lack confidence in detecting and responding to it, due to limited education that rarely goes beyond validated tools and practical skills. Comprehensive training with evidence-based screening tools and intervention strategies would provide nurses with the proficiency to manage cases efficiently. Scenario-based learning should be included to test providers against real-life complexity when patients or other stakeholders are involved.

Routine adoption of gambling-related harm screening within services is also needed. Standardized protocols across healthcare facilities—from primary care offices and mental health clinics to emergency departments and financial counselling—would ensure consistency. Integrating assessment tools into electronic health records would normalize and simplify the process, making risk assessment routine rather than specialist. Standardization would not only increase true positives but also address disparities across sectors.

Once risks are identified, transparent and accessible referral pathways are critical. Professionals often hesitate to engage because they don’t know where to refer people. Creating efficient referral structures with culturally appropriate services and specialist networks would bridge this gap. Pathways must be inclusive, ensuring vulnerable groups such as ethnic minorities or rural populations are not left behind. Growing specialist networks and guaranteeing navigable referrals would turn detection into meaningful care. Together, these changes would shift healthcare from crisis management to early, preventative intervention.

In addition to health reform, effective harm reduction requires regulation that forces the industry to take responsibility for how it markets and profits from its products. Operators have adopted advanced technologies for user engagement, while regulation lags in preventing exploitation of cognitive biases and vulnerable populations. Greater scrutiny in promotional standards, technology assessments, and industry-funded education would create a more rational system.

New marketing standards are required to restrict psychological levers that drive participation. Many adverts exploit authority appeal, scarcity framing, or illusory control. Regulators could demand psychological impact assessments for campaigns, as is done for pharmaceuticals. Screening young adults, those with financial stress, and people with prior addictions remains essential to protecting at-risk groups. Advertising rules must prohibit misleading portrayals of gambling as a legitimate income source or risk-free entertainment.

Emerging technologies such as virtual and augmented reality also demand oversight. While they may shape new gaming cultures, they heighten vulnerability by blurring play and reality. VR/AR platforms should be obliged to assess the risk of harm, with guidance on time limits, spending caps, and user protection warnings. Without safeguards, immersive environments could intensify problem gambling on an unprecedented scale.

Regulation must also require the industry to fund professional education and research. Supporting ongoing education for healthcare staff would keep them current on screening tools and interventions. Allocating a percentage of gambling revenue to independent research would build the evidence base for future policy. Directing industry gains into prevention and education would help design a more equitable, sustainable system.

These reforms would not stifle innovation but align industry expansion with public health, ensuring consumer protection remains paramount.

All analyses of behavior related to gambling have inherent methodological constraints, which are more accentuated when integrating knowledge across disciplines and types of data. While the current work combines theoretical perspectives from psychology, economics, health sciences, and industry literature, integrating insights from disparate disciplines is not without its difficulties. The standpoint of disciplines varies in the conceptualization of gambling-related harm–psychology with cognitive bias, economics with the market structure, and medicine with treatment outcomes. Combining such perspectives enhances the knowledge, but it also increases the possibility of concept dissonance since the theoretical frames and measurement instruments often do not match.

A second limitation is the sample size. With the empirical strand of this study consisting of just 89 subjects, statistical power is restricted. Although qualitative data offer richness, the modest sample size limits generalizability, particularly for various cultural and socioeconomic groups. Larger, more representative samples would provide greater confidence in findings, particularly for the exploration of subgroup analyses examining differential vulnerability to gambling-related harm.

Another problem is the rate of decay of market data. Betting markets move fast, as new technologies and regulations change online behavior in real time. Even games from just a few years ago can feel terribly outdated, especially within fields such as mobile betting or VR casinos. This prompts us to think about how much we can learn from history and highlights the importance of ongoing data collection.

Lastly, the difficulty of generalizing findings from a laboratory setting to elsewhere should be acknowledged. Controlled experiments are necessary to separate out cognitive mechanisms like the gambler’s fallacy, but such conditions are unlikely to reflect the complexity of real-world gambling environments in which social influence, exposure to advertising, and financial circumstances play off against one another. This gap has proven a fundamental methodological challenge for the field.

While the current study provides valuable insights, several avenues of research remain critical for advancing understanding of gambling-related harm. The development of prospective, longitudinal studies that measure the relationship between market dynamics and public health outcomes takes priority. Short-term analyses miss how behaviors are not stable, while long-term tracking could show how changes in regulation, product innovation, or marketing intensity translate into addictive behavior, and thus financial stress and demand on health care.

Secondly, that is technology-specific studies. The cognitive biases that inform how players think and act are being expressed in new ways. For instance, the gambler’s fallacy within a virtual reality casino could come into play in forms not observable in the traditional world. Empirical evidence that teases apart these effects will be important in the development of prevention efforts for new technology.

Also, we would need to pay more attention to cultural differences in gambling-related harm. The overwhelming majority of the existing literature focuses on Western settings, but cultural norms, religious attitudes, and regulatory climate differ widely between societies. Cross-cultural comparisons would not only increase generalizability but also contribute to the identification of context-specific protectors or risks.

Lastly, future research should examine time-varying effects of interventions. The use of screening protocols, public awareness programs, and regulatory changes is frequently introduced without systematic evaluation. A longitudinal tracking of outcomes—from gambling prevalence rates to help services engagement—could then establish an evidentiary basis on which to refine and justify policy interventions.

Together, these research priorities would help the field progress to more precise, context-based, and future-oriented strategies for gambling harm reduction.

We’ve always had a paradox with gambling in society; on the one hand, it’s entertainment that we celebrate, and on the other hand, there’s quite a range of harms at an individual and community level that are caused by gambling. The present research aimed at investigating how cognitive biases, industry landscape, and healthcare response intertwine in a process where the psychology of fear (vulnerabilities) is utilized as a means to exploit and control, in a backdrop where defense systems are trying to catch up.

At a deeper level, the continued prevalence of the gambler’s fallacy and these associated biases reflects the inadequacy of human cognition when it comes to understanding randomness. Then, as now, people are driven by the same spurious intuitions; from the classic Monte Carlo incident of 1913 to the current lack of betting options you’ve been presented with, the desire to feel in control is as strong as ever. Although probability theory has long refuted the myth that random events “balance themselves out,” players frequently play on gut instinct rather than math and therefore remain vulnerable to a damaging cycle of chasing losses down the drain. Cross-domain evidence from sports, finance, medicine, law, and meteorology further supports the universality of these biases, suggesting that it is not gambling that is risky, but a system that is designed to exploit humans’ susceptibility to risk.

The growth of the industry has exacerbated these issues. VR and AR bring a new level of immersion, mobile offers quick-fix play, and the scientific sophistication of marketing campaigns, from celebrity endorsements to loadable targeted digital ads, targets our brains’ well-documented weaknesses directly. Such transformation, due to the fast pace of the development of these strategies, generates a gap between consumers’ vulnerability and the regulatory protection.

As policy measures around monitoring and intervention battle to keep pace with the challenge, many harms inevitably surface only far into the process (by which time damage is often extensive), due to a lack of resources, patchy training, and long systemic slippage. So there are desperate policy implications, and they are multi-dimensional. For healthcare, better training, standardized screening protocols, and clear referral pathways would bolster front-line responses.

On the regulatory ledger, reforms must ensure that industry innovation does not run ahead of what the consumer can control. Marketing guidelines that incorporate sensitivity to bias, harm evaluations for new immersive technologies, and required funding for education and research are policy moves that would help recalibrate the larger system. Crucially, they must work together and not in isolation; the issue of gambling-related harm is clearly too complex for isolated approaches.

Methodological considerations and limitations of this study have been recognized. The difficulty in merging data across domains, the limitations of a small sample size, the dynamic nature of market data, and the challenge of generalizing findings from the laboratory to the field jointly delimit the current set of conclusions. Nevertheless, these constraints also directly highlight future research needs. Longitudinal research on the relationship between market and health, bias analyses of technology-specific technologies, cross-cultural comparisons, and intervention evaluation would help to fill important evidence gaps and provide the basis of more informed policy and clinical response.

In the end, it’s a message that the research coalesces around: gambling harm isn’t simply a matter of individual frailty or bad choices. It is the result of systemic incentives that benefit from cognitive biases, technological affordances that magnify risks, and institutional failures that slow or weaken proactive interventions. Dealing with this, consequently, is much more than programs; it’s actually a reset of the incentives, wherein growth must be met with comparative investment in guarding the consumer, the capacity of healthcare, and evidence-led policies. In summary, the way forward is to consider gambling as a public health and public policy issue rather than as an economic or entertainment issue only.

By weaving together perspectives from the fields of psychology, medicine, industry, and regulation, it may be possible to develop a framework wherein we preserve personal freedom while reducing avoidable harms.

Disclaimer: All news published on Times Of Casino is provided for general informational purposes only and should not be considered legal, financial, investment, or professional advice. While we strive for accuracy, the online gambling industry evolves quickly, and information may change. Times Of Casino is not liable for any losses resulting from the use of this content. Readers are advised to verify information independently and consult professionals before taking action related to casinos, its affiliates, or gambling services.

Why Trust Times Of Casino: All products and services featured on this page have been independently reviewed and evaluated by our team of experts to provide you with accurate and reliable information. Learn how we rate.

See less